Mahler and Meta: Is AI art?

How Technology Shatters the Limits of Expression.

Art is not a product, but a problem. If art is emotion on a medium, it has always been shaped by the tools available to humans. These tools and techniques could impose technical constraints on artistic expression - we have pointed arches and buttresses to thank for freeing us from dark and heavy Romanesque churches and bringing us airy Gothic naves - slowing down creativity.

Occasionally though, new tech engenders entirely new ways for humans to embody their ingenuity. Photography is a clear enabler for the imagination. But did you know that early photographers sometimes intentionally blurred their photos in an attempt to imitate oil paintings, in the face of relentless criticism of their medium and before we accepted the potential of photography as a new vehicle for art? The tension between incumbent artists and newcomers goes back much further than the explosion of AI.

Roughly half a century separates the death of Julia Margaret Cameron and her Pre-Raphaelite photos and the birth of Robert Mapplethorpe.

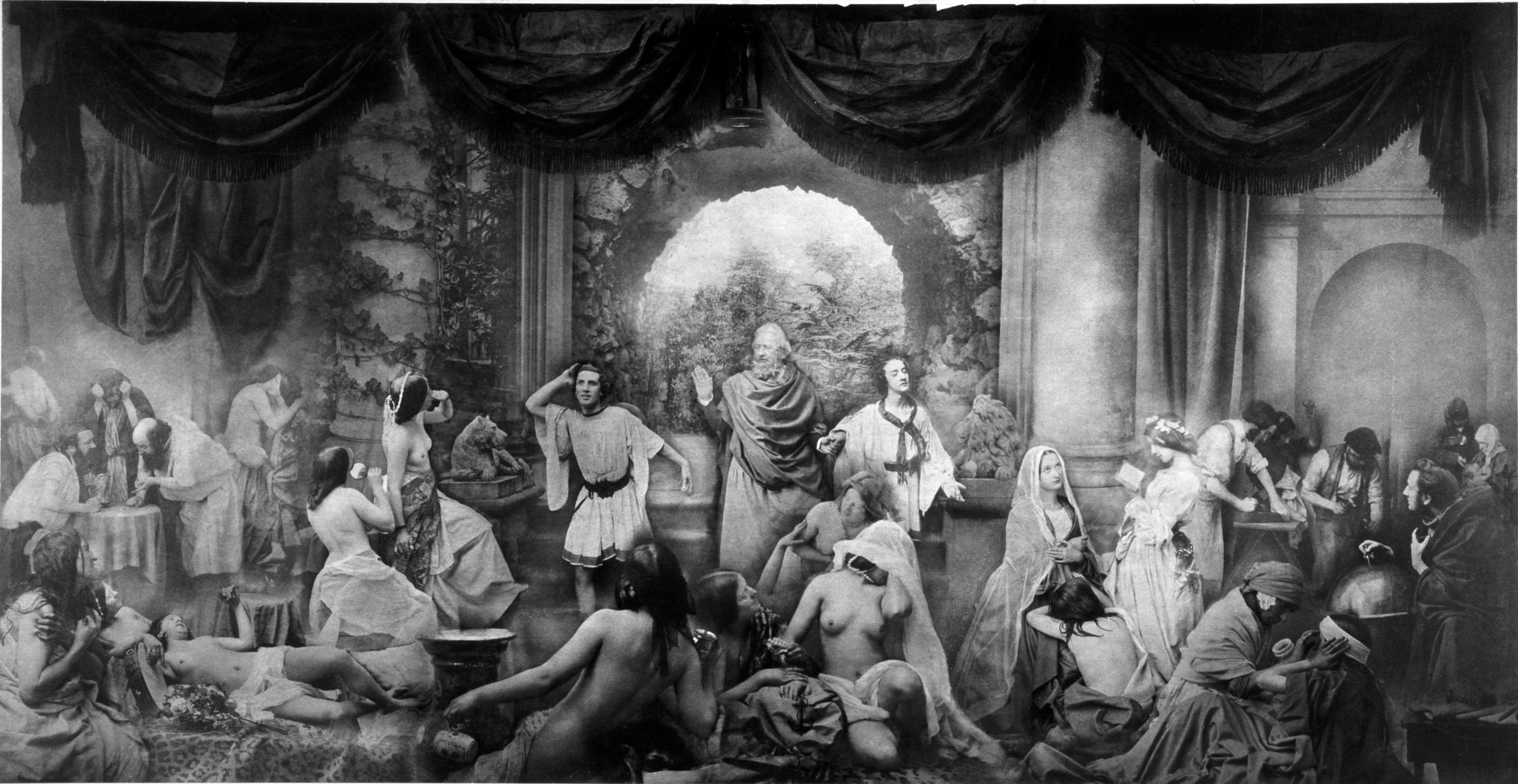

Julia Margaret Cameron's 1867 portrait of her niece, Julia Jackson – mother of Virginia Woolf. Julia used soft focus, long exposure times, and staged compositions to create pictorial effects that resembled Pre-Raphaelite paintings. She also added scratches, stains, and texts to her prints to enhance their artistic quality. Photograph: National Media Museum, Bradford-Science and Society Picture Library. As for Mapplethorpe, imma let you Google that one.

I was inspired to write this article after playing around with Meta's MusicGen tool to create new bits of music out of text prompts. Did you know that Mahler composed a pretty jazzy piano concerto? I mean, he didn't, but I'm going to see some jazz at Vortex on Friday and I love Mahler, so I wanted to give Mahler the chance to enjoy that breathless coked-up gremlin-performer quality I've experienced every time I've been to Vortex.

Ancient Art and Technology

The biggest truths are so obvious that we don't stop to think about them ("This is Water" by David Foster Wallace). So it's powerful to stop and consider how the dawn of art coincided with the dawn of technology. One of the earliest examples of how technology influenced art is the invention of writing. Writing enabled not just the transmission of stories and ideas beyond the limits of oral tradition, but it also enriched other forms of art such as painting and sculpture, by providing symbols and inscriptions which added meaning and context to visual representations.

Egyptian hieroglyphs, for example, are pictorial representations of words, sounds, or concepts. But they were used to decorate monuments, relief sculptures, paintings, metalwork, and jewellery. They not only added meaning and context to visual representations, but they also had an aesthetic function, as they were often arranged in harmonious and symmetrical compositions.

Another early example of language helping to evolve other art forms, the François Vase (c. 570 BC). The vase illustrates episodes from the Trojan War, the Calydonian Boar Hunt, the Return of Theseus, etc. But it also contains inscriptions that name most of the characters and some of the events depicted on the vase, expanding the limits of oral tradition like a Hellenic hieroglyph

Another example of how technology influenced art in ancient times is the development of metallurgy. Metallurgy fostered metalwork and jewellery as forms of art, using metals to craft shapes, patterns, and designs that reflected the culture and aesthetics of each civilization.

Modern Art and Technology

Few examples illustrate the many ways that technology influenced art in the modern era as the invention of photography. Photography revealed reality in unprecedented detail and speed, spawning a new art form where subjects could be more raw, narratives gleaned from ordinary moments of day to day life. Needless to say, photography also challenged other forms of art, such as painting and sculpture, by questioning their role as the primary channels of representation.

Famously, photography was not immediately embraced as an art form by the traditional art world. Many critics and painters dismissed photography as a mere mechanical reproduction that lacked creativity and originality. The French painter Paul Delaroche famously declared that "from today painting is dead" after seeing a daguerreotype in 1839. Similarly, the British critic John Ruskin argued that photography was "not an art but a science" in 1853.

Photographers also faced challenges in developing their own style and identity as artists. Initially, many photographers tried to imitate the conventions and techniques of painting by using soft focus, long exposure times, staged compositions, and color filters to create pictorial effects. It took decades for the world to truly see the potential of this new medium.

The Two Ways of Life, a moralistic photo montage by Oscar Gustave Rejlander, 1857. Rejlander used combination printing, angles, light sources and even editing to create large-scale and elaborate compositions that resembled historical paintings.

Another example of how technology influenced art in the modern era is the development of steel structures. Steel structures and lifts enabled the first ever skyscraper in Chicago (the Home Insurance Building) and thus a new language for architecture. Steel structures also challenged other forms of art by providing new materials, spaces, and contexts for artistic expression (did anyone go to see the BBC Proms at Printworks?? or have you been to Bold Tendencies? Hearing Messiaen in such an unpretentious setting rearranged my brain chemistry).

It was a Frenchman, the writer Émile Zola, who described the Eiffel Tower as "a hideous and colossal skeleton", noting its industrial look. It was another Frenchman, Le Corbusier, who took 'industrial' as a compliment and proposed to raze Paris to built his machines for living (apartment blocks) 50 years later. Paris is truly at its best without Parisians. But I digress.

Generative AI and art

So: can machines make art?

In form, they sure reflect human-produced artwork. That's because AI models are drawing from humankind's body of work. There are valid questions about originality, copyright, and self-sabotaging. How will art evolve if we flood the internet today with many-fingered regurgitations of existing work? How will case law keep up with copyright? How about monolithic Napoleonic legal systems?

My biggest qualm with questions of copyright is that artists have always benefitted, including commercially, from the work of previous artists. There have been cartoonish depictions of other cultures' art borne out of racist, atavistic orientalism (often in the defence of empire). There has been relatively respectful discovery and reinterpretation (see Picasso and African art). There has been outright provocation (I refuse to post a picture of the Koons vs Rogers controversy because Koon's work belongs on top of a 90s Serbian TV set, doily permitting), and there has been the most comical analog precursor to the current copyright controversy, when Anish Kapoor tried to copyright the 'blackest black'.

Gathering Clouds I-IV by Anish Kapoor, 2014, fibreglass and paint, via the artist's website.

Assume the medium enables. Does art require human intention? Jean-Michel Jarre declared "AI is not an artist" in 2019. And yet, anyone who has spent hours refining prompts, iterating on outputs, rejecting hundreds of generations to find one that captures a specific feeling, knows that intention finds its way in. The human isn't absent; they're conducting.

Medium versus intent versus emotion versus audience utility

What if an AI prompts another AI? Is the product art? The language model writing the prompt is drawing from a breadth of recorded human experiences and emotions I'll never get to partake in. The neural network (GANs, VAEs, transformer models) using this prompt to generate an image is also looking at all the recorded human artwork. There is, or has been, human emotion, There is, or has been intent.

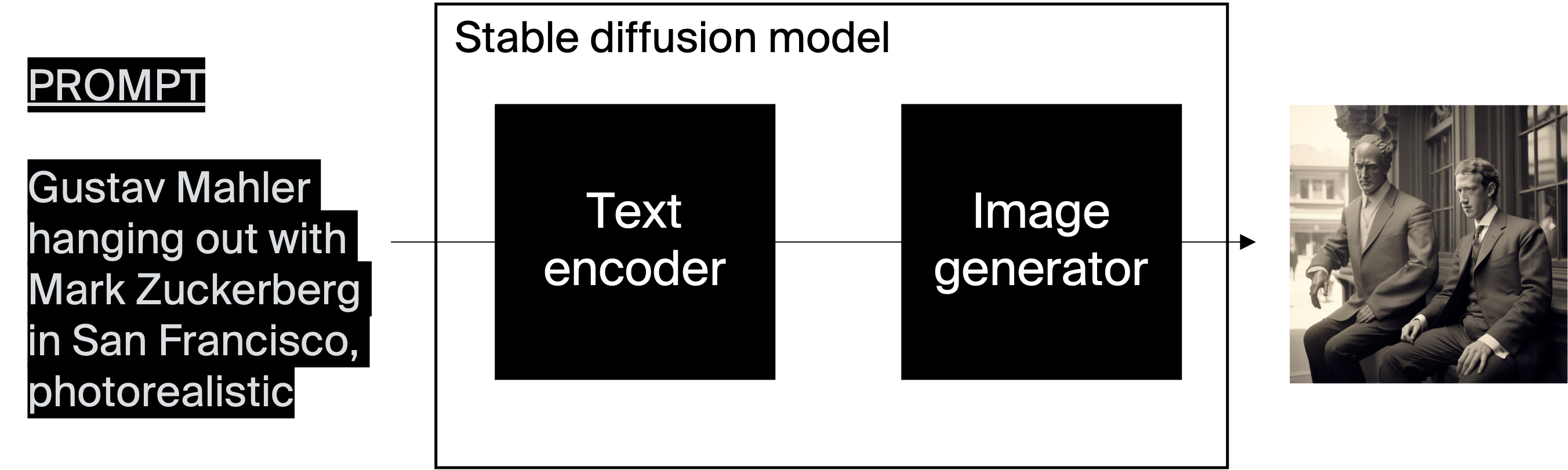

This is the high level of how a stable diffusion model works. Text prompts get converted into tokens (units of information that the model understands); this gets 'understood' by an encoder, which then parses the latent space of all information to come up with a set of instructions for the image decoder.

What if an AI prompts and AI, which prompts an AI, which prompts an AI… One can assume that if we add enough steps, human emotion, intent, and even form will be progressively less recognisable. I don't worry about form; we don't admonish Jackson Pollock or Marcel Duchamp for taking tremendous leaps in form (at least not anymore); we praise them. I do wonder about emotion and intent.

Imagine a house built by machines on an uninhabitable asteroid. No human will ever use it. Is it still a house? For robots, it might serve a utilitarian purpose. For humans, its meaning is purely representational: a concept made manifest. The artifact's nature depends less on who made it than on who encounters it. This isn't a new problem. Ask your parents whether graffiti is art. The answer often reveals more about the audience than the work.

Artists deserve fair compensation for their work. Full stop. But we can't forever prevent machines from perceiving the world, including existing artworks. We're deploying sensors and automations everywhere. The difference between a camera and a generative model is that the latter is proactively fed training data; the trajectory, however, points in the same direction.

Current case law also doesn't really lend itself to recognising copyright infringement if the new artwork does not appropriate all or most of someone else's earlier copyright work, but instead uses inconsequential elements of it together with other images created by the new author. By the very way that encoder-decoder architectures work (eg, stable diffusion models), there is abstraction and original creation.

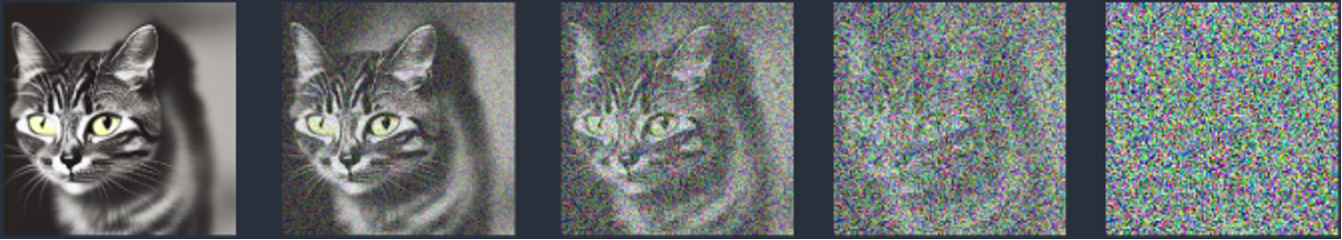

When training a model, we 'diffuse' an image by adding random noise to it in steps, and teaching a predictor how much noise was added at each step. Reverse diffusion consists of starting from complete noise and then taking away noise step by step based on the amount of noise our predictor tells us there should be at each step. The randomness innate to this process means it's extremely unlikely that generic prompt instructions for a 'painting of the Thames in London at dusk' will return a painting by Canaletto exactly.

Conclusion

Technology and art have been intertwined since the first hand pressed pigment onto a cave wall. Each new tool provokes new expression. How we assign worthiness, intent, emotion, form, and effect will shape the economics of creation and, perhaps, our very enjoyment of art. Two things seem clear: artists remain essential and deserve fair compensation for their work. And generative AI expands what creation can be, though not necessarily what it should be.